Confessions of a Lousy Language Learner

A veteran excuse-maker recounts his linguistic failures

My reckless path to multilingual mediocrity

This is part 2 of being a bad language learner

Let me summarise part 1, Why Some People Suck at Learning Languages thus:

I squandered the opportunities I had as a youth while living in Europe, and the best language practice I found years later as an adult was speaking French to some stoned North and West Africans in Montpellier.

You want some good, unorthodox strategies? Try any of these:

Find yourself a romantic partner. An ex-girlfriend studied abroad in Russia and right away found herself a non-English speaking boyfriend. For about a year she put up with him (poor dude) in order to perfect her Russian. It worked. She was a bit of a mercenary, this woman.

Live with a granny. A former colleague moved to Moscow and lived with a babushka for a while and by the end of his stay he spoke fluent, grammatically flawless Russian.

Flirt with foreigners in Irish pubs. A former Ukrainian student had excellent pronunciation. Her secret? As a teenager, talking to foreign men in Irish pubs in Kyiv, mimicking their pronunciation, and getting bought loads of free drinks. It probably helped that they were attractive.

If you’re unable to do any of those things, then you’ll have to find other means of learning the language. And this requires time, motivation, discipline and patience.

And need, though some might quibble over this.

In his stellar post, How to Be a Good Immigrant,

discusses the importance of learning the language:“I find that individuals believe that they will fail to learn a language either because “it’s too hard” or because “I’m not talented enough”. This, in my experience as a language teacher of twenty-five years, is, to use a technical term, bullshit. If you fail to learn a language, it will almost always be due to one of two factors: putting in too little effort, or poor language instruction.” (my emphasis)

And, “the two big obstacles to overcome when you arrive in a new country and start learning a new language are (a) finding the right teacher or method, and (b) finding opportunities to practice.” However, these obstacles can be overcome, if you adopt a permanence mindset and commit to spending both time and energy on learning the language.”

In part 1,

of the excellent Rootless in Italy newsletter categorised language learners in the comments:The Survivors – For them, it’s a matter of necessity. They’ve moved to a new country and have to learn the language in order to live, work, and function day to day.

The Intellectuals – They’re in it for the love of the language itself. They find the structure, history, and nuances fascinating, and enjoy the process of studying it as an academic or personal pursuit.

The FOMO-driven – For lack of a better term, these folks hate the idea of being left out. If they’re abroad, they need to understand what’s going on around them. It’s less about survival or pure interest, and more about staying in the loop and feeling connected.

That said, let’s move on and examine (and laugh at) my pathetic excuses for my abysmal language learning efforts and yes, I will blame others along with myself.

Poor language instruction: the bad teacher – or rather, absent teacher

Lviv, Ukraine, 2005: I was motivated and there was a clear need since very few people in the city spoke English and almost nothing from restaurant menus to street signs was in English. If I wanted to talk to people outside of school, I’d have to learn Ukrainian.

I also came to Lviv because I was fascinated by Ukrainian history and culture and wanted to put in the effort to master the language.

My school provided 10 free language lessons in either Ukrainian or Russian.

Very few people then – and even fewer now – speak Russian in Lviv.

I had a lovely colleague, Ella, and she was the designated Russian teacher. She was so eager and enthusiastic to teach me, but I resisted her overtures. ‘No thanks, I’m here to learn Ukrainian.’

Unfortunately, the designated Ukrainian teacher was unreliable as hell. Constantly cancelling lessons last minute. Putting them off. Not showing up at all. I arrived in late August and didn’t have my FIRST lesson until mid-November!

I’ll be mature and take most of the responsibility here. I could have been more pro-active and demanding, but I’m not much of an initiative taker and although I was half-heartedly studying Ukrainian on my own, I was passively waiting for this teacher to whip me into shape and kept telling myself, ‘okay, when I start with her, then I’ll push myself.’

In the meantime, I figured I could find a non-English speaking girlfriend, so I asked out a woman from the gym. She brought her friend along, ostensibly as a translator, but as it turned out, this friend was vetting me as a potential marriage partner, peppering me with all sorts of questions about my salary, goals, prospects, potential…

‘Um, check, please?’

A woman on a trolleybus gave me her phone number. We exchanged a few texts, but they were indecipherable. A colleague said she probably hadn’t enabled the Roman alphabet function on her phone, or there was a problem with my phone. Or she did this intentionally as a polite way of turning me down.

I think we’d had only 3 lessons by the end of December and maybe 1 or 2 in the new year, but that was that, I never finished my allotment.

As for a need, there was and wasn’t one. I went out with teaching colleagues and some of my students a lot, and they all wanted to speak English, and I met one or two locals who spoke good English. Other than my failed attempts at romance, I got by just fine, and then eventually went out with a woman who spoke passable English and then later said ‘to hell with it’ and just dated a colleague.

As bad a language learner as I am, I always make sure I have the basics down.

The permanence mindset

I knew I was only going to be in Lviv for 9 months. So, once it got to January, close to the halfway point of my contract, my motivation waned even more as I considered options for my next destination. When I first started teaching, it was meant to be for two years, and I had no idea where I’d end up later on. I remember thinking, ‘will I need Ukrainian again in the future?’ and quickly deciding no, I wouldn’t.

Well now…

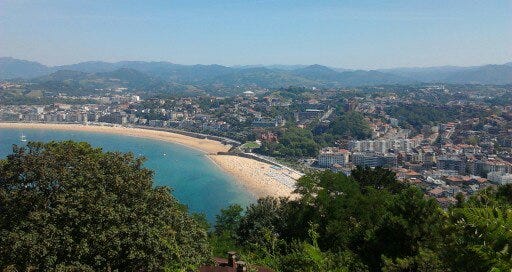

San Sebastian, Basque Country, 2006: I decided right away that I wasn’t learning Basque, as cool as that might have been. I figured I had enough Spanish from my past and just needed to brush up on it.

I got by with my basic, functional Spanish with no additional motivation to improve it. I socialised with colleagues, so there was never a need to go beyond ‘dos crianzas, por favor.’

I also had a miserable time there (that’s a long sob story) and was counting down the days until I left, furthering eroding my motivation.

Riga, Latvia, 2007: I was back in Eastern Europe, in a place where geopolitical tensions meant there was a divide between Latvian and Russian speakers. The vast majority of our students and my colleagues were Russian speaking though the places in town I frequented were mainly Latvian speaking.

The school offered 10 free Latvian lessons. I took one even though I wasn’t so keen on learning Latvian. It was a good lesson. The teacher was lovely and I sent her a message asking for private lessons, even though I was more interested in her than learning Latvian.

She never responded.

Influenced by a Scottish colleague who was fluent in Russian, and thinking pragmatically, I opted to study that instead. I figured I was likely to use it more in the future.

But again, my efforts were half-hearted at best because I never socialised with Russian speakers or frequented Russian-speaking places.

June 2008: I left Latvia and went on holiday to Crimea, Georgia and Armenia. I figured I could use my Russian a bit.

In Crimea, however, being in Ukraine again and feeling nostalgic, I defaulted to what little Ukrainian I knew, the pleasantries at least. That did not go down well in Sevastopol. I bumped into some drunken, rowdy sailors at one place, who didn’t take too kindly to my use of Ukrainian.

Outside of Yalta, I took a cable car to a cliff-top Tatar settlement and it was a welcome relief to be able to use my paltry Ukrainian.

In Georgia and Armenia, people didn’t mind my attempts to use Russian and I managed okay.

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, 2009: I proved to be a decent language learner after all.

With time to kill before starting my post-graduate teaching certification in September, I headed out to Central Asia in January with two clear goals: to teach English one last time, and to properly learn Russian.

You can read about the three Russian teachers I had in an earlier post, but by the time I left Kyrgyzstan, my Russian wasn’t too shabby. While traveling alone through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, I had no problem getting by and even found myself engaging in deeper conversations with locals. I got embroiled in tense negotiations with one woman who wanted me to marry her daughter and was deeply offended when I politely declined.

My language skills were really put to the test in a matter of life and death on a 10-hour taxi journey across Kyrgyzstan, in a taxi winding through narrow mountain roads during a rainstorm. Our pious driver stopped periodically to pray and was also falling asleep at the wheel. We offered him a Pepsi to stay awake. He declined. Repeatedly. Politely. Then angrily.

Meanwhile, my friends Brian and Kristen and my sister were in the backseat quietly bracing for impact, and I was up front making small talk with the driver to keep him conscious. This led to a surreal conversation about whether Brian and Kristen were in a serious relationship (they’re now married), and if my sister was single.

And then, just to round out the vibe, our sleepy, saintly chauffeur pulled out his phone mid-drive to show me two things: Boney M music videos and, horrifyingly, child pornography. It was like he was trying to hit every square on the ‘worst taxi ride imaginable’ bingo card. Between the rain, the cliffs, the unsolicited smut, and the disco soundtrack, we were all silently preparing our final thoughts.

I left Kyrgyzstan with decent Russian and a girlfriend – the aforementioned [English] one who found the boyfriend for language practice – who spoke it fluently. We talked about the possibility of working in international schools together, but in the meantime, she went back to the UK to do her master’s, and I went to the US for my teaching certification.

After a few months of the long-distance thing, she dumped me, and I’m not even sure why I’m including this here other than to elicit a tiny bit of sympathy.

Kyiv, Ukraine, 2010: I’m so sorry, my dear Ukrainian friends and readers, but on my return to Ukraine I wasn’t messing about and taking my chances and I opted to continue with my Russian. I wanted to build on my existing knowledge and was determined to keep at it.

And I think I did. I’m usually an anti-social misanthrope, but I’d sidle up to the bar and make small talk with barmen all the time. Some of the best speaking and listening practice came at local markets where I’d haggle over every fruit and vegetable known to mankind (this is also highly underrated language practice, especially for numbers). I also had a conversational partner and we’d alternate between English and Russian on nights out. She was impressed.

I even had a date one Sunday morning where in my hungover state, I spent 3 hours as the only man in an art therapy drawing class. I can’t even draw shapes and squiggles and describe them in English, let alone Russian, but somehow I survived and understood everything clearly, getting some bonus psychotherapy in the process.

‘So, Daniel, all these black, sinister shapes? Hmm…that portends deep-seated neuroses and spiraling doom and gloom. You’re screwed, buddy.’

Not much need

In the run-up to Euro 2012 (the European Football Championships, co-hosted with Poland), two things happened:

1 English was sprouting up everywhere in street signs, menus, shops and cinemas.

2 I met the woman who would become my wife and she spoke English.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but one of the key differences between Western and Eastern Europe, if I break it down into crude generalisations, is that in Eastern Europe, people are more eager to learn and practise English. In my travels in Western Europe, locals rarely if ever wanted to speak English. In Ukraine, so many people were desperate for any practice that even when I started speaking Russian, they’d answer in English.

It got to the point that when my girlfriend and I went to cafés or restaurants, they’d automatically hand me an English menu (where I could make fun of all the egregious mistakes – a language salad? Herring under fur coat?). The waitstaff would either address me in English, if they knew it, or ignore me altogether and talk to my girlfriend/wife: ‘So, what will the foreigner be having?’

Once again, when your motivation and initiative is already shaky, I wasn’t persistent in my attempts to improve my Russian.

As the years progressed I gave up on improving, and I also made feeble attempts to learn Ukrainian but now I’m a sad specimen of a language learner.

Russia invades Ukraine, 2014

Up until 2014, Kyiv had always been a city full of Russian speakers and barely anyone batted an eyelid. After Russian invaded Eastern Ukraine and Crimea, many Ukrainians consciously started speaking Ukrainian more. That meant I used my Russian even less, but still didn’t make much of an attempt to improve my Ukrainian.

Why not?

Let’s continue with the excuses/reasons/justifications:

The opportunity cost

As an insatiable reader, any time not spending reading books in English fills me with all sorts of existential dread, sending my crippling anxiety into a tailspin. I have lost so much sleep over the realisation that I won’t live long enough to get through my TBR list and read all the books I want to read.

The same applies to writing. I’m trying to make up for lost time and get all these books churned out, and I’m wracked with anxiety if I’m not writing, a process I otherwise fine pleasurable.

I’m easily distracted and I find it blissful to not understand people in public

In a café in a foreign country, with people jabbering away unintelligibly, I can peacefully go about my business of reading or writing. Once I hear English, my concentration is shot and I start getting fidgety. This is why I don’t enjoy cafés in English-speaking countries very much. I can’t concentrate at all. Trains in foreign countries are perfect for reading; in the UK, unless it’s the quiet carriage, it’s in vain.

The conversations I often hear in English tend to be pretty banal, and I say this as a lousy conversationalist myself.

It befits my image of the permanent outsider, the global citizen without a home

This goes back to previous posts about me, the outsider, not having a home and not feeling at home anywhere. Belfast is probably the closest thing I’ve had to home over the years and I haven’t even been there since 2006 when my grandmother died. But it’s where I spent the most time over the years and the only consistent place where I could return to whenever I wanted.

Now, I find myself in a cosmopolitan city full of international organisations, where the bumbling expat with poor language skills is king (or queen). This is what I’ve become and honestly, I’m so worn out and jaded from life going in unexpected directions and plans going pear-shaped that I barely have the time to write, look for work, or sleep, never mind learning German.

What about German?

Three years in Austria and I barely speak any German.

I didn’t expect to leave Ukraine and end up here, and I’ve been busy feeling sorry for myself (I exaggerate) since arriving that I’ve had little to no desire to learn German. Anyway, in Vienna, almost everyone speaks good English, which also has its downsides: it’s hard to find work here as an English teacher.

I can also live vicariously through my daughter. She’s 7 and speaks English, German and Russian fluently, and we’re working on her Ukrainian (she understands and can read it fine). She’s sort of my teacher/translator in public and she enjoys making fun of my abysmal pronunciation.

Lately, however, my daughter has taken it upon herself to teach me German. So now, as I check her homework, I diligently repeat after her and I’m slowly picking up words and working out the grammar rules.

Everywhere I’ve gone, I’ve learnt enough to survive, but I’ve accepted that, due to my work ethic, lack of motivation, psychological makeup (anxiety/fear over not being able to read and write enough) and the lack of any immediate need, I’ll never get to a level where I can truly appreciate it.

I know so much has been said about language and culture being inter-linked and how learning the language helps you truly understand the culture. And I accept that I’ve perhaps only had a superficial knowledge of the places I’ve lived. But I appreciate the history and non-language culture of everywhere I go, and I feel like I have a decent understanding of Ukrainian life and culture. But others might say otherwise.

Anyway, that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Feel free to berate or defend me in the comments.

In case you missed it

My last post introduced my new project, Drinkglish. Next week I’ll be dropping the next episode (isn’t this what the kids say?), featuring a chat with a Substack legend.

You can find my Drinkglish channel on YouTube here: watch me!

What may make it difficult for Americans to learn a second or third language is that they are not exposed to other languages when they are young. In Europe there is a Bologna agreement where the EU made a policy that advises learning three languages at least: your own country’s, a neighbouring country’s and a third one. Many choose English as the third language. Children start in primary school with their first English lessons.

Up till the 1970s in many countries, e.g. Belgium and the Netherlands, we were taught 4 languages standard: German, French, English and Dutch. And did exams in all 4. At least it gave you a broad base in linguistics and made it easier to learn new languages. If you attended a Gymnasium or Grammar Schook, you also learnt Latin and Greek. Therefore in Europe, being able to speak several languages is a sign of being civilised or having had a good education. Only the Brits are an exception. In the EU it is inconceivable to go the uni speaking just one language.

That means a totally different attitude to learning languages.

Love these confessions, Daniel! It's so refreshing to hear someone being brutally honest about their misgivings abroad. You've definitely gotten creative in a different ways that you've tried to learn! I was really hoping my son would be my translator too, it's not happened in thailand, but maybe he'll pick up Spanish easier. 😅😅