Is being accurate and ‘correct’ in English always so important?

It depends – forgivable v unforgivable mistakes

No, no, no Katy…home to where, exactly?

In this post, we start with less serious forgivable mistakes from non-native speakers of English, before moving onto far more serious unforgivable mistakes from native speakers (who ought to know better).

Part 1: Go easy on them – they’re foreigners, they’re trying

Some months ago, visiting my doctor, the tables were turned, and he was the one asking me for a diagnosis – he was worried about his “bad English” and whether he needed lessons. He even offered to hire me (I should have said yes in exchange for free visits).

I asked him what he needed English for. Was it for professional or personal reasons? Purely professional: he was concerned that he couldn’t communicate accurately with foreigners.

I told him he didn’t need lessons at all. That his English was perfectly adequate for his purposes. Even though I’m a trained English teacher, I assured him that no one should have any trouble understanding him.

So what was his concern? That he was making too many mistakes and lacking the right vocabulary.

Did he make some mistakes? Sure. Was his grammar accurate? Not 100%, but mostly. Pronunciation? He was easily understandable. Vocabulary? More than enough to get the job done. Did he understand me and his other foreign patients clearly? Yes.

“Really?” he asked me. “Everything I say is okay?”

“Absolutely,” I answered. And this was my honest professional opinion. I wasn’t being lazy, and I wasn’t going to lie to him just to make some extra cash. I laid out the reasons and he seemed satisfied.

In linguistics there’s a term called mutual intelligibility, which basically means ‘if I can understand you and you understand me, that’s fine.’ This is often used for pronunciation and for language learners struggling to improve their pronunciation, and it’s fine if you don’t ‘sound like a native speaker.’ You don’t have to, and you’re not expected to.

My first doctor in Kyiv back in 2010 wasn’t a native speaker, but nor was he Ukrainian. His English was generally fine (though his ethics were another matter). He had trouble pronouncing some words, but in medical English, that’s normal, especially if you’re stressing the wrong syllables or using Latin names. But he did seem to struggle with basic vocabulary, pronouncing knee as ‘KUH-nee’. That’s fine. Less reassuring was his mixing up of elbow and shoulder (which might explain why his treatment was so unsuccessful).

This brings to mind a lovely idiom that my grandmother always used: “He wouldn’t know his arse from his elbow.”

As long as you know your arse from your elbow, and if you’re simply looking to get your message across, you’ll be fine with occasional mistakes.

I refer to mistakes as forgivable and unforgivable. My doctor makes forgivable mistakes. Foreigners conversing in public make forgivable mistakes. Here are just two examples I overheard in a café a while ago:

“As a teenager, I always must to turn off the light.”

“She is not scientific person at all.”

I sometimes call these ‘painful foreigner conversations’, and I don’t mean that in a disrespectful “look at those idiots making mistakes” kind of way. I admire anyone able to communicate in a foreign language (I’m hopeless at other languages). These are forgivable mistakes – no one is going to be seriously offended or misunderstand anything.

If you want to do some eavesdropping, you can listen in on English conversations to (a), work on your listening skills (with different accents, native or non) and (b) see if you can spot any mistakes. If you’re feeling really bold and ambitious, you could (c) interrupt them to gently ‘correct’ their errors.

For example:

“Hi, I couldn’t help overhearing you talking about your teenage years, my parents were strict like yours and I always HAD TO turn off the light as well.”

Two common mistakes being made here: using to after must/should/can/might; and not realising that the past tense of must is had to.

“Did you say your friend is not scientific at all? I have a friend who’s a very scientific person. And my ex-boyfriend is really scientific person.”

Well done to this person for using at all correctly, which is a typical mistake for some learners (it’s almost always used in a negative sense, with not: I don’t like football at all). Otherwise, the most natural way to say this is ‘She is not scientific at all’ but how about this option for spicing things up: ‘She is not at all scientific.’ Try using at all in the middle of your sentence for a change.

Part 2: Even native speakers get it badly wrong

In my book I talked about how plenty of native speakers make basic grammatical mistakes and use simple vocabulary much of the time. As an example, listen to any British footballer being interviewed and you’re bound to catch a handful of terrible language examples.

(It’s actually wonderful listening practice, by the way, to listen to a range of British and Irish accents: Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, along with regional dialects. I bet even my American audience – and I know there are plenty of you – would struggle with some Scottish accents. As a challenge go to YouTube and look for some Gordon Strachan interviews and I dare you to understand every a single word he’s saying.)

During the last World Cup, one of my students (a star journalist) was interviewing Declan Rice and she asked him whether he knew any Ukrainian words (because of his Arsenal teammate, Oleksandr Zinchenko).

His response: “I’ve not learned no Ukrainian words yet.”

Oh no, the dreaded double negative! He hasn’t learned ANY Ukrainian words yet. Kateryna, being the excellent journalist, stellar student and proud Ukrainian that she is, then taught him “Slava Ukraini,” which he pronounced decently. (Zinchenko was then supposed to teach Declan the appropriate response, “Heroyam Slava,” but I’m not sure if she followed up on that.)

Declan’s mistake is sort of forgivable, but it just goes to show no one is perfect, especially with pronunciation. I saw a commercial recently on American television related to paying off debts, and one of the speakers, an American, pronounced it like “de-Bht”, stressing the ‘b’, which is something every teacher would correct in a student. Compare: debit (de-buht) and debt (deht).

Forgivable, but barely. Also in that category, this headline: “Some Things I Wish I Would Have Learned in College.”

Any good learner would notice right away that it should be “Some Things I Wish I HAD LEARNED in College.” He’s American, so a British person might say “Some Things I Wish I Had LEARNT in UNIVERSITY.” But now I’m just nitpicking.

By the way, read this post, from finance writer/blogger Ben Carlson. It’s very good, and if you can forgive his incorrect headline (and if you’re British, his overuse of gotten), it’s very educational:

Some Things I Wish I Would Have Learned in College

(However, you can sometimes use would after I wish: I wish you would do your homework! I wish my students would listen to my advice! I wish the US and Europe would get their act together and give Ukraine everything they’ve got to wipe out russia so this war would be over and done with!)

How about this gibberish, from the BBC? You would certainly expect a lot better from them, wouldn’t you?

Out of context, it’s somewhat unforgivable. It looks like gobbledygook - I think I know what they were trying to say, but this is utter nonsense. It was live text, during the Euro 2024 final, so it was rushed. But are there no editors to quickly double-check?

The point is, we’re all human. We all make mistakes.

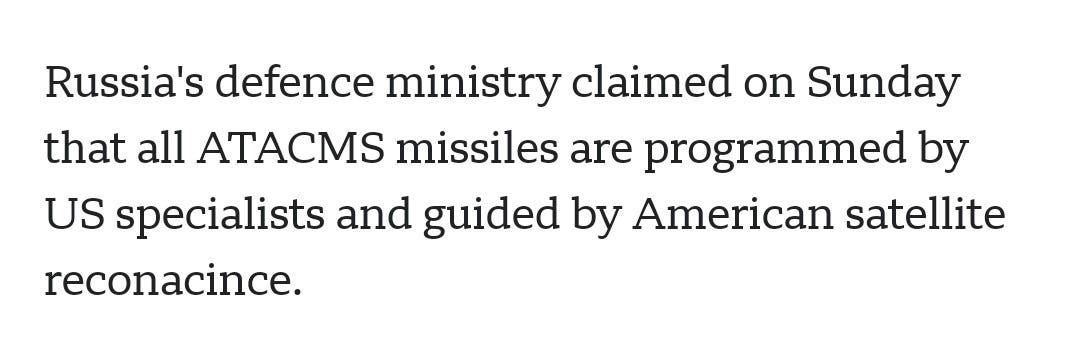

But this? This is, to use a big word, utterly egregious, again from the BBC:

Reconacince? What are we doing here, going for the phonetic spelling? Who on earth wrote that, and where on earth are the copy editors? It’s reconnaissance!

My book covers many of these themes across a range of chapters: why you shouldn’t worry about mistakes, managing your expectations, the range of your vocabulary (and how what you know is probably already more than enough to get by), the quirks and oddities of English and much more.

There’s also an entire chapter dedicated to the differences in American and British English, namely past simple versus present perfect and the use/overuse/misuse of the passive.

Here’s a recent headline from The Atlantic:

In Ukraine, We Saw a Glimpse of the Future of War

I can’t help analysing language – this is what teachers often do, even in their spare time (I think – maybe it’s just me). My first thought when seeing this headline? Oh, the war’s over now?

Trust me, it isn’t. But that’s a misleading headline.

Technically, it’s not grammatically incorrect, and we’re now touching on language and cultural stereotypes. American English doesn’t tend to feature the present perfect as much as British English. To me, an avowed follower of British English, this use of the past simple Saw implies that the war is over. Once again, we know that’s not the case, unfortunately. Therefore, it should read, “In Ukraine, We Have Seen a Glimpse of the Future War.”

I’m going to call this a borderline unforgivable mistake. Many might not even notice any issues, but I certainly do. It’s very misleading and I’d even argue that in American English it’s wrong. Honestly, Atlantic (and I’m an avid reader), where are your copy editors?

Onto our final example, and we’re into prime 100% unforgivable mistake territory.

I love the passive and get irritated when my wretched [American] grammar check tells me to change it to active. No, damn it, leave my passive alone! For anyone who has used Grammarly, you will have experienced this (it follows American grammar rules). English teachers in the US often tell their students not to use the passive voice.

In the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom, teachers explain that we use the passive when the result is more important than who committed the action, or we don’t know who committed it. So, instead of saying “the Wright Brothers invented the airplane in 1903” we should say “the first aeroplane (sic) was invented by the Wright Brothers.” But the Wright Brothers are important figures and so it’s worth mentioning them by name as well.1

Another example: “Last night, a man was attacked and robbed.” That’s fine, for the most part, since the important thing – the subject of the sentence and the action – is the man. Who attacked him? It might not matter. Written in the active voice, it might read “Last night, somebody attacked and robbed a man.” That sounds odd to my ears.

We can add some more details: “A man was found beaten and robbed in an alleyway last night.” But I think we still need the passive.

But what about this: “A man was attacked and robbed by a gang of penguins in an alleyway last night.”

Now things are getting interesting, and we have to ask, as a headline writer, what’s more important: the man who was attacked or the fact that it was a gang of penguins who attacked him (or even, who he was attacked by)? Better might be: “A gang of penguins savagely attacked and robbed a man in an alleyway last night. The man was found with beak marks and covered in penguin droppings in the early hours…”

As much as I love the passive, way too much of it is used by way too many newspapers (or rather, way too many newspapers use it). There are many cases of this, but it’s the Kakhovka Dam destruction just over a year ago in June 2023 that got many people rightfully riled up.

I’ll pick on the The New York Times here, though there were plenty of others who did (and continue to do) the same: “The Kakhovka dam on the Dnipro River was destroyed on June 6…” and “Thousands of residents fled rising floodwaters in southern Ukraine, a day after a dam on the Dnipro River was destroyed.”

Why are they using the passive when we clearly know WHO did this?

Fine, let’s be flexible here: use the passive if you must, but say WHO did it.

Moving away from the passive, too many newspapers have simply been way too wishy-washy with their language (on Twitter, some have called this ‘media malpractice’). Other absurd examples include, from 12 June: “A disaster unfolds in slow motion after a blast destroys the dam at the Kakhovka Reservoir, emptying its waters and threatening livelihoods and industries crucial to Ukraine.” A blast? But where did this blast come from?

Now we jump to 18 June: “Evidence suggests this month's destruction of the huge Kakhovka dam in a Russian-controlled area of Ukraine resulted from an inside explosion set off by Russia…”

Active, passive, whatever you use, cut out the ambiguous diplomatic language. I don’t think it’s any better to say, “Ukraine suggests Russia was to blame for the Kakhovka Dam explosion.” Suggests? There’s nothing here to suggest – just tell it like it is in a to-the-point headline: “Russia destroys Kakhovka dam.” That’s it. How hard is that?

Totally unforgivable.

A final unforgivable mistake

I have to pick on Katy Perry, my daughter’s favourite singer here. Shame, shame on her for this tweet:

I don’t think anyone from England, Wales or Scotland would ever forgive her for this.

Thanks to those who have got my book and if you’re still hesitating, two things: one, I’ll continuing donating 100% of my royalties to Ohmatdyt Children’s Hospital in Kyiv for another week and two, if you’d like to read a free chapter – the one on British v American English – send me a message and I’ll be happy to send it to you.

Happy reading.

This is something I occasionally did in my book to highlight the differences in spelling: airplane (US) v aeroplane (UK)

So, what's Katy P mistake? It's about the difference between going home and coming home? Or she should have added a specific place "Football is coming home to England"

Thank you!

I readed your latest blog!